|

History of Virtual Cities

Martin Dodge wrote a nice history of virtual cities back in 1997 and extended his perspective in an Atlas of Cyberspace that he completed in 2004. People have been painting urban settings as long as they have existed. Had we had the luxury of supporting a town painter to capture our cities as a library of paintings from different angles around town, we could assemble those pictures for a walk-through experience today. Perhaps a service like flicker.com will someday exist for all the artistic sketches and paintings artists did of city centers. Those artistic renditions are likely to help us reconstruct our historical virtual city versions.

Some of the first on-line virtual cities were make-believe. As the History of MUDS states, Multiple User Dimensions (MUDS), such as the

first ever text-adventures like Colossal Cave and Adventureland[,] were not exactly based on complex quests; they relied instead on an old principle very dear to Western civilization: go there, take all the treasures you can collect, and come home filthy rich.

|

|

3-D Web History |

Building Virtual Cities |

Viewing Virtual Cities |

Virtual Cities History |

Historical Preservation |

More Links...

And yet, they often contained virtual cities in which you could travel north, east, south, or west one step at a time. These cities were described by text and yet contained descriptive components familiar as being part of the city schema. They did not let you explore textual models of real cities. That would have been of very little use unless the reader scribbled a map out by visualizing line by line. The MUD interface did not describe precision or a clear relation of one place to another. Wayfinding in a physical city would be difficult to do if given only a MUD to explore beforehand.

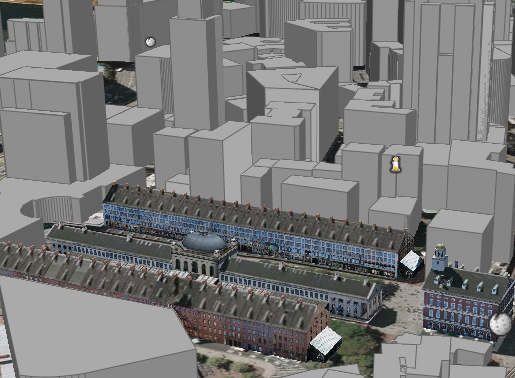

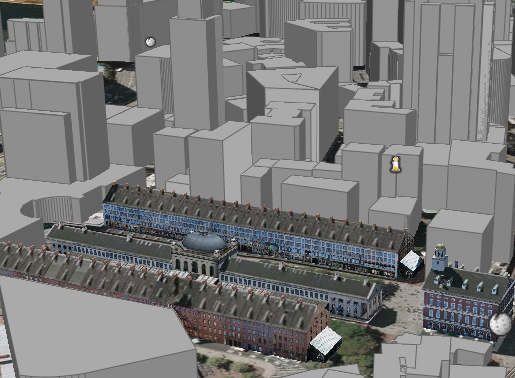

As graphic capabilities become more commonplace on home personal computers, virtual cities began to appear as visual entities you could explore with your keyboard and mouse. They still tended to be make-believe, but applications were being developed that suggested the need for real virtual cities.

The flight simulator became more interesting as you could fly over models of real cities like New York or San Francisco. As Story of Flight Simulator states, the application has been around for a long time:

In the mid-70's Bruce Artwick was an electrical engineering graduate student at the University of Illinois. Being a passionate pilot, it was only natural that the principles of flight became the focus of his master's work. In his thesis of May 1975, called "A versatile computer-generated dynamic flight display", he presented a model of the flight of an aircraft, displayed on a computer screen. He proved that the 6800 processor (the first available microcomputer) was able to handle both the arithmetic and the graphic display, needed for real-time flight simulation. In short: the first Flight Simulator was born.

As race car video games became more popular, modelers became obsessed with the realistic look and behavior of the cars. As the Gran Turismo 4 article states online:

Steven L. Kent, author of The Ultimate History of Video Games, recalls that when the groundbreaking original Gran Turismo was being crafted, the game's accuracy-focused developers test-drove each of the 75 cars that would appear.

"If in real life the car could go zero to 60 in five seconds, in the game, you better believe that car would go zero to 60 in five seconds," Kent said.

It wasn't long before the same passion in modeling the race cars extended to the environment in which they raced. The virtual grand prix race circuits faithfully attempted to reproduce the city tracks in which the races were run. The virtual city skyline attracted players to the games.

While the video game industry may have pushed the virtual city development initially, urban planning and architecture departments in academia began to consider how virtual cities could help visualize design alternatives.

|