What is the

Simulaton Life?

The simulaton life is a rich life experience provided by training our

minds to consider simulations of natural and human phenomena often

in order to gain depth in understanding, awareness, and compassion.

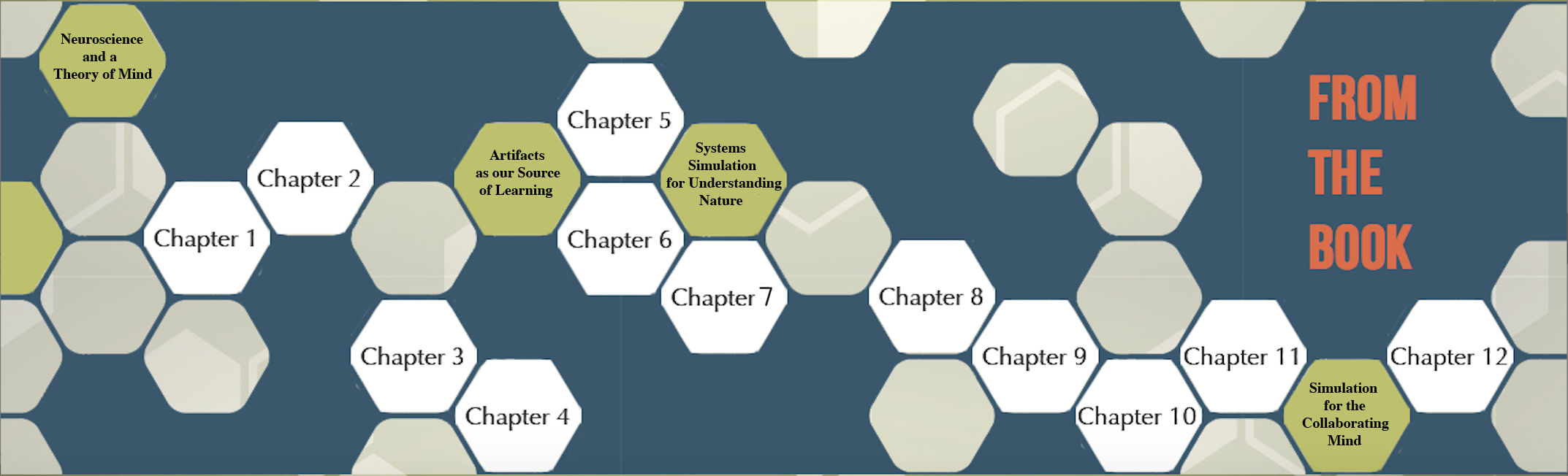

From the Book

Book text is in a living document format, licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. In other words, you are free to share this work for non-commercial purposes as long as you don't create derivative works of this material, attribute me as the author, and keep this license notice intact. For more information about this Creative Commons license, please visit: http://CreativeCommons.org.

Chapter 3

the embodied mind

Now that we've had time to contemplate how our senses provide our brain with the inputs from which we can create our simulated reality (chapter 1), and we've had time to contemplate a theory of mind as an example of what the brain can do with sensory inputs to evoke thoughts and behaviors (chapter 2), we'll spend some time in this chapter contemplating the ramifications of our mind as embodied within the brain-body system.

The embedded mind concept suggests that the mind is embedded in the body in a way that the mind's development is highly dependent on the experiences the body makes available to it. There are more formal definitions provided by terms such as embodied cognition, but the gist is that we would not have a mind, as we know it, without the body providing the brain experiences in which to form a mind. There are many corollaries to explore that come from a hypothesis that the mind is embedded in the body — such as one that suggests the quality of the experiences we encounter drives the quality of the mind we possess.

Francisco Verela et al's book entitled The Embodied Mind starts off with reasoning that supports investigating an embedded mind hypothesis well:

Minds awaken in a world. We did not design our world. We simply found ourselves in it; we awoke both to ourselves and to the world we inhabit. We come to reflect on that world as we grow and live. We reflect on a world that is not made, but found, and yet it is also our structure that enables us to reflect upon the world. Thus in reflection we find ourselves in a circle: we are in a world that seems to be there before reflection begins, but that world is not separate from us.

It's useful to revisit the current theories of how our senses work. Embodied cognition is easier to contemplate once we're familiar with human senses — our body does a lot before our brain begins to process stimuli from the world around us. To consider the embodied mind hypothesis, we consider the human senses to be by-products of a functioning human body (the eyes, ears, hands, nose, tongue, etc.), as made available to the brain. Each new signal received from our senses provides the mind a component on which to build itself.

The embodied mind hypothesis overlaps with an embodied cognition hypothesis. In philosophy, the embodied cognition hypothesis holds that the form of the human body largely determines the nature of the human mind. Philosophers, psychologists, cognitive scientists, and artificial intelligence researchers who study embodied cognition and the embodied mind argue that aspects of the body shape all aspects of cognition. The aspects of cognition include high level mental constructs (such as concepts and categories) and human performance on various cognitive tasks (such as reasoning or judgment). The aspects of the body include the motor system, the perceptual system, the body's interactions with the environment (situatedness) and the ontological assumptions about the world that are built into the body and the brain.

To consider the possibility that the embodied mind hypothesis is true to a significant extent, I spend time assessing my day-to-day experiences to figure out the contribution each makes to my mind. Since some of the most significant experiences seem to have happened when I was young, I try and recreate those experiences as simulations through a mix of memory and imagination so I can investigate what each experience may have contributed to my mind at that time. Some of those simulations include details that seem contrived, but there are examples of some that seem lucid as if the original had happened much more recently.

As an example of an experience I keep lucid, I often replay the experience of the first time I saw a movie in a theater. I was two months short of turning five years old. My mother's best friend celebrated her daughter's fifth birthday by taking a bunch of young kids to see The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn on the big screen. As I remember it today, the word movie was just two syllables of sound with no meaning at the time to me — just like the world bowling was until I participated in my best friend's birthday party at a bowling alley. I appreciate the fact I remember my introduction to the movies so vividly, but I am surprised those to whom I ask about recollections do not. Perhaps it was due to the ear infections I experienced so readily back then and the variety of hearing experiences that caused — my ears were clear and working well for my first movie experience.

As I remember it as if it played out in slow motion, we all walked into a rectangular room with seats mysteriously bound together — all facing in the same direction. The lights were dimmed slightly but the whiteness of the four walls around me suggested that I was in a safe place with safe people. We sat down without much conversation and all stared forward at what I now call a big white screen (I had no words for it the time). I remember squirming in my seat a bit as the lights proceeded to dim until near darkness. Were we really going to sit in the dark, facing away from each other, at a birthday party?

Wham... A huge vivid scene of some green woodsy place filled my field of vision — vivid as could be before the days of high-resolution and Dolby sound. I'm pretty sure those few seconds literally blew my mind. Loud sounds hit me precisely as the picture began to make some kind of sense. I don't remember which emotion bubbled up first, but I know fear was a significant emotion at some point early on. I can remember I sat there with a sense of insecurity, even though I didn't have that word in my vocabulary at the time. If something like this could sneak up on me at a birthday party, what might sneak up on me in life where celebrating a birthday wasn't the theme of the moment?

Experiencing Huckleberry Finn comes back whenever I spend time thinking about our minds and how the human brain does what it does. Based on what I've read and remember experiencing that day, my mind made a quantum leap in development during the course of one film (with one twenty-minute intermission). The drastic end of the film's projection before the intermission period was another shock to my mind's flow. I imagine myself living at a time when such a drastic immersion of my senses was not possible during waking hours. I don't think my mind would ever have developed to the point of incorporating what I was forced to make sense of during that first adventure movie. Before movies, how would all our senses have been transported to such an artificial, yet literal, view of someone else's development — in a different time and place?

In the context of the simulaton life, each movie provides the mind a new experience from which to develop the mind — by being present with all the faculties of the body. Huckleberry Finn takes place in a place I had never experienced physically and a time from history I will never experience physically. Though I would never have the opportunity to experience a movie for the first time again, I can recreate the feeling of that first time when I want to remind myself of the potential each movie provides my mind's development. Each movie that captures my focus as an audience member provides a significant experience from which my mind forms as an ongoing ally (or nemesis) in creating my quality of life.

At times it seems like my being wants to move on and forget about that first movie experience and yet I have continued to recount that experience and remind myself often enough to be able to experience it viscerally on demand. Other people I talk to about that seem to have moved on long ago without such a vivid memory of the experience. I chalk that up to the differences in dispositions among people. My experience would be deemed sensitive using the vocabulary of experts who study those differences. I like to think that sensitivity lets me develop my mind better through new experiences as I am more likely to revisit and recount those experiences until I have generated all the insight and understanding I can. But, I realize there are a lot of experiences where I am not particularly sensitive at all. Moviemakers strive to make me sensitive through story-telling and sensory experiences. I can tell they are effective at it whenever I walk out of a theater pondering a film for days afterwards — on subjects I never would have anticipated having much interest beforehand.

It's possible that I am sensitive to many forms of simulation beyond the film medium, which would explain some of my interest in writing this book. As I throw my body into new simulations — whether via movies, stories, dreams, or advanced computer simulations of complex phenomena — I find there is an opportunity for my mind to expand and develop each time the simulation presents a new component to consider. There's a keen awareness when a simulation has changed my thinking or provided richness to my process of thought. Sometimes I am aware that my brain is active trying to contemplate the simulation but the insights and understanding is yet to emerge. There is a sense of that which comes similar to when I am using muscles in physical exercise. The embodied mind hypothesis suggests that's a highly useful way to develop my mind — to throw myself into situations where my brain encounters simulation through processing of my senses. The more the embodied mind hypothesis is significantly true, the more the simulaton life can help me develop my mind.

The more I can effectively communicate my mind through artifacts that embody my thought processes, the more I can hope to awake other minds to similar thoughts. The culmination of embodying minds in artifacts results in supporting related hypotheses such as augmented cognition and distributed cognition. There is compelling evidence for those hypotheses as well. We'll consider the hypotheses this chapter and follow-up with the artifacts in the next.

The hypotheses supporting augmented cognition and distributed cognition have been tested through novel techniques by determined researchers. Their findings can be told as a series of stories with conclusions — stories that perhaps deserve a better theatric media for your consideration, but which can hopefully turn your brain here well enough.

Edwin Hutchins performed his research on the distributed cognition hypothesis — a hypothesis that suggests a brain does not need any mystical internal cognitive processing in order to make sense of the world. Hutchins suggested all the cognition could be explained through experience with physical objects, abstract artifacts, and social communication (social cognition). To investigate the hypothesis, he studied complex activities that required coordinated teams of people to see how the knowledge necessary to perform the activity was distributed. He spent long periods working with activities of piloting ships and airplanes.

As he studied the activity of bringing a large ship into port successfully, he found he could map the cognition needed to the three categories of cognition: object, artifact, and social — none of which takes place without use of basic brain-body services. Since he studied a naval ship coming to port, he had the benefit of studying an activity that had been highly designed over time to be effective and efficient — effective to provide safe arrival to ship and crew and efficient to save time and money in doing so. The humans had been trained to perform their duties well in narrow but well-defined roles that take advantage of the benefit of a military hierarchy where following orders are highly regarded among participants. The proper social behavior among participants had evolved to be highly defined when performing the activity of bringing the ship to port — corrective actions taken were highly practiced, trained social behaviors. The physical devices (like compass and telescope) have clear interactive components that provide a shared cognition just through their current configuration. Other more abstract artifacts (like maps and ship blueprints) provide the last of the shared cognition necessary to bring the ship to port.

Roger Pea performed his research Roger Pea on a distributed intelligence hypothesis (the differences of which are immaterial for our purposes here). He studied primary school classrooms to identify how students learned. Through a process of observing all tasks and activities within the classroom, he clearly identified well-known learning activities where the functional manipulation of representational states must have occurred within the mind of an individual student because they were alone with no external objects or artifacts at the time in which to offload cognition (in Hutchins case those situations had been eliminated by design). He compared the rate of learning (which for our purpose we can substitute insight and understanding) between classrooms with object and artifact learning aids to those without such features. He looked at social cognition as well — from the standpoint of a teacher interacting with students, and students interacting with students. He found great advantages to learning environments where social cognition, object cognition, and artifact cognition were optimized on behalf of the student's learning process.

Gary Klein spent a long time researching fire fighting teams and their approach to putting out fires. Through a well-documented longitudinal study, he offered a recognition-primed decision-making hypothesis that the study's data supported well. The hypothesis plays well with a pattern-recognition theory of mind in that it states: the built-in ability of humans to find patterns in complex data suggests we have a built-in penchant for matching patterns of complex perceptions to thoughts about the significance of our current state. Fires occur often enough that a senior firefighter has the opportunity to perceive enough fires under a wide-enough variety of conditions in order to connect his pattern-recognition ability to his comprehension of what is going on and to his projection of what to do about it. Since fire fighting is often an activity performed under duress, quick decision-making is required. The fact that decision makers reported they just "knew what to do" almost immediately suggests they had honed a pattern-recognition ability in their minds — at least within the scope of fire fighting. The hypothesis resonated well enough with the fire fighters that today, if fires are not occurring regularly, training regimens allow for minimally-controlled fires to be set in order to gain the requisite experience. Fire fighters who want to gain experience often look to move to districts where fires are more regularly experienced in the environment.

As we did last chapter, we've reached a point where we can agree that each sub-hypothesis that support an embodied mind hypothesis provides further exploration for us to gain further insights and understanding of the ramifications. There's just enough in here to suggest the embodied mind hypothesis may be true. Let's continue by contemplating the embodied mind as a concept to see what else comes from it.

Extensions to the embodied mind hypothesis suggest simulations (as objects and artifacts containing social cognition) can be helpful for communicating knowledge across minds — especially when a shared artifact can facilitate interaction with the human body. The social nature of human beings suggests humans will readily share the insights and understanding they gain from simulation exposure if they are given the opportunity to do so with others who are enthused to listen and relate. Chapter 11 looks at social media as an emergent platform for sharing insights and understanding.

Hutchins, Pea, and Klein performed their research following a scientific method that has wide acceptance as being a valid approach to testing hypotheses. Varela provided a compelling argument for first-person observation to gain acceptance in the field of neuroscience as a secondary point of view worth considering. I like his arguments because the embodied mind hypothesis resonates as I experience my mind in action. Having been trained in the scientific method, I have been troubled by the fact that I cannot yet reach a scientific belief that the embodied hypothesis (and related sub-hypotheses) is true — the means for fully testing of the embodied mind hypothesis are emerging slowly. I want the scientific evidence to support the hypothesis in order to better support my conviction for a simulaton life.

Thanks to the simulaton life providing me such pleasure, I have lived a life that begs I take a leap of faith to believe in the embodied mind, regardless of the lack of objective evidence. My personal subjective evidence, in addition to the objective evidence so far, has become enough for me. The life I have lived following the embodied mind hypothesis has consistently resonated with a quality of life I have wanted with less impact on the planet. The life I lived in the physical world has produced more waste and destruction. I seem bound to pursue the simulaton life as if the embodied hypothesis were theory even if scientific evidence suggests a different hypothesis tests better. My convictions may suffer some consequences and this book may be less useful as a result. I will keep updating this book to incorporate all evidence made available to me — including that from readers like you.

Requiring the scientific method as an approach to understanding our minds has led to a bias in where we put our focus within the domain of cognitive science. If cognitive science is the domain of all aspects of mind and thought and how mind functions, we have spent an inordinate amount of time researching the specifics of cognitivism — the hypothesis that cognition is the manipulation of symbols through mental representation. Since digital computers process primarily through symbolic manipulation (structures of 0s and 1s we give meaning), we've had good tools to study the potential of cognition as cognitivism. Since our progress seemed quite promising, we invested a lot of time and money into applying scientific method to its pursuit. In retrospect as we contemplate cognitivism, the original digital computers appear to provide a trajectory towards minds without bodies. And, yet, the field of robotics received a great boost in advancements once we gave those computers bodies with which to interact with the world they were symbolically representing.

As I think back to the source of the tools I use for symbolic manipulation, I can anticipate a benefit of tying those symbols to real world objects. If I attempt to do the addition of 3 and 5 in my head, I can see a benefit of mapping the symbol 3 closely to three fingers and the symbol 5 to five fingers — there is a sense of embodiment providing me my first steps towards being able to add two numbers together. As the symbols become more abstract, I cannot tie the ability to manipulate the symbol to my first embodiment of the symbol, but I can imagine that I did so at some point. I can imagine the possibility that my mind could not represent the symbol without the embodiment of its representation somehow. And yet, digital computers reliably manipulate symbols tirelessly without a body — perhaps that means they manipulate the symbols without cognition.

An alternative to the cognitivism approach to cognition is an emergent approach to cognition. The emergent approach seems relevant when we investigate how our brains make sense of all the little electrical impulses coming in parallel to be processed from our sensory organs. Certainly the electrical signals are small bits of information coming in all the time, and yet we have a continuous consciousness that seems to simulate the world around us seamlessly from those bits. A benefit of emergence is that our cognition can proceed usefully even if one small piece of the data is unclear (cognitivism on the other hand depends on precise symbols that manipulate erroneously when not represented correctly).

The embodied mind hypothesis suggests that the experiences we have (or better the experiences we find ourselves in with our body) are at the core of our ability to understand, contemplate, and project the future of phenomena we think about. In many cases, the embodied mind even influences which phenomena we think about. Had I never been introduced to virtual reality, even without the experiences being immersed in it at a research lab, I doubt I would ever have conceived of virtual reality even though it seems quite obvious as a thought in retrospect. It's difficult to believe that humans didn't think about the wheel before being introduced to it, but someone must have made the first wheel at some point and it's hard to imagine people thinking about it for a long time before being able to create one upon thinking about it.

The embodied mind hypothesis rescues me when I think about how long I've taken to settle on a career path. I've dallied at five degrees in five different subject matters with just a marginal level of overlap. Although I never thought pure academic pursuits were for me and I worked full-time while pursuing degrees, I would probably feel a stronger guilt of putting all that time into independent thought if I didn't believe that my mind was being developed through sitting among corpus of professionals in five different professions. There is no doubt that accountants and financiers developed my mind very differently than computer scientists — no doubt that information scientists developed my mind very differently than systems engineers. I am never surprised to see such confusion in meetings where all five professional groups are trying to collaborate over some issue like land conservation or community water quality. In those rare occasions when professions are willing to listen to each other, my mind flutters from perspective to perspective with a certain lack of certainty as to which perspective is correct.

The embodied mind hypothesis also rescues me when I begin to feel badly about all the carbon dioxide my travels around the planet have contributed to the atmosphere — or all the fuels I have used that could be used by future generations. Whereas many of my friends will likely travel more often after raising their children, I will have traveled in lieu of raising children. And, if the embodied mind hypothesis is true, I will have the benefit of having put my body in all those cultural experiences early in life — my mind will carry those experiences with me for the duration. It sure feels like I could shut down the travel cold turkey for the rest of my life and still get the joy and perspective of thinking about the travel for the rest of my life.

The more living true to the embodied mind hypothesis provides me a diversity of thought and experience, the more I am willing to put myself into foreign situations — often with a role I imagine as anthropologist trying to explore a new culture in order to makes sense of it in my mind. I can see that I am not as competent as those who are experienced with the situation, but I feel strongly that I have unique points of view because I have lived through a series of experiences that no other human being has experienced — and we can all say that as there are so many new experiences (like the first movie) that we are exploring to which no other humans in history have had access.

The embodied mind hypothesis suggests that we humans are getting smarter as a by-product of experiences becoming more accessible to us all. Food experiences have exploded for us, even as we limit our shopping to local supermarkets. First person bodily interactions have exploded for us as video games have let us throw our bodies into the game.

Although the embodied mind suggests we are getting smarter even without thinking about getting smarter, my sense is that we get smarter even faster as we think about getting smarter through each bodily experience. The nature of my doctoral dissertation work required that I work with a community of people who spend their lives becoming better meta-thinkers — thinkers who become better at recognizing how they are thinking. Professional analysts in financial and government roles spend a lot of time questioning whether they bring mental biases to the process of analyzing data. They focus on understanding the processes their minds have followed to reach conclusions from a train of evidence. If I had already developed meta-thinking skills as a five year-old, I would perhaps have a better recollection of how my mind incorporated the experience of cinematic movies into my worldview. Having worked to develop meta-thinking skills, I sense I have a strong ally with which to investigate experiences that shed light on how the embodied mind works.

As we continue reading, we'll build a case for facilitating our embodied minds through external artifacts we strategically embed into simulations of phenomena we're interested in understanding better. Meta-thinking is just one skill we can improve through more explicit uses of our brain capabilities. By tying our meta-thinking to visual artifacts and interactive simulation experiences, we provide a feedback loop for stimulating our brains further as we pursue a train of thought that provides new insights. Next Chapter