What is the

Simulaton Life?

The simulaton life is a rich life experience provided by training our

minds to consider simulations of natural and human phenomena often

in order to gain depth in understanding, awareness, and compassion.

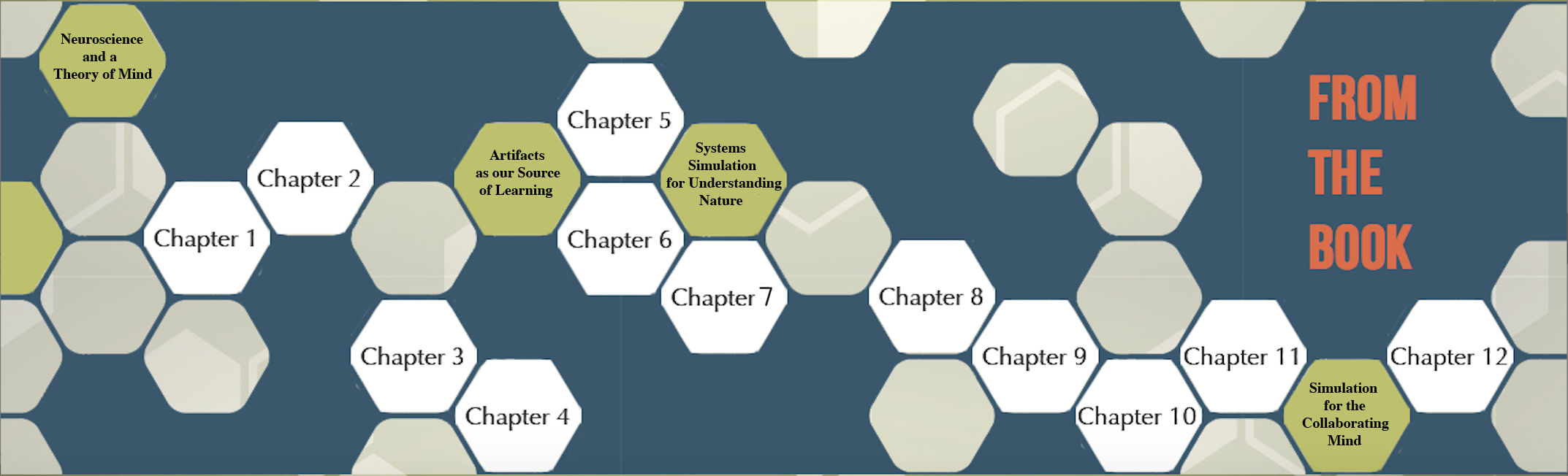

From the Book

Book text is in a living document format, licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. In other words, you are free to share this work for non-commercial purposes as long as you don't create derivative works of this material, attribute me as the author, and keep this license notice intact. For more information about this Creative Commons license, please visit: http://CreativeCommons.org.

Chapter 4

artifacts as our source of learning

Chapter 1 suggests we buy into the idea that our brain provides us a useful simulated reality through the beneficial consideration of inputs from our senses. Chapter 2 suggests we buy into a theory of mind as a reasonable process by which we combine basic stimuli hierarchically into complex objects to make sense of the world around us. Chapter 3 suggests we buy into an embodied mind theory to contemplate how our world grows through the experiences we have been privy to. This chapter suggests we apply the perspective of the first three chapters in order to appreciate the value of those objects in our environment that turn on our ability to think in new and insightful ways to increase our understanding.

The Oxford dictionary provides two definitions for the word artifact. One definition suggests an artifact is an object made by a human being, typically an item of cultural or historical interest. The other suggests an artifact is something observed in a scientific investigation or experiment that is not naturally present but occurs as a result of the preparative or investigative procedure. We'll try and explore a potential intersection of both definitions where we suggest humans should more often explicitly pursue artifacts that provide insights that aren't usually generated by other means — in order to deepen our understanding about the context of the artifact. I'll suggest such artifacts are then worthy of significant interest.

Human artifacts embody knowledge. Historically, we have investigated human artifacts to ascertain what knowledge existed in the community that created the artifacts. Or we investigate the artifacts to ascertain what that community valued or did in the past. Today, perhaps in anticipation of future anthropologists, we create an artifact to represent an understanding we have or to encourage shared investigation of significant phenomena in our lives. We use artifacts to broker knowledge and the pursuit of knowledge. The form of artifacts is changing and yet we build new artifacts out of a base of successful artifact components of previous communities. Written language is an example of a hierarchical base for artifact generation. Musical and mathematical notation are examples as well.

One of my favorite examples of a powerful object to encourage thinking is a map. Maps give us the ability to change our perspective so that we can consider geography from different scales, depending on how we want to think about the world. As I look at maps of the world that provide labels of places in the native languages of the peoples that exist there, I get a certain perspective of the complexity of landforms. At the same time, I get grounded in a consistent configuration of shapes that help me recognize relationships between land and ocean. Over time I recognize patterns of geography faster with a broadening extent. As I limit the geographical extent on a map, I get a more immediate focus of a place and can think about an extent I don't normally have access to in my day-to-day locomotion. Upon familiarizing myself with geography, I can add layers of information on a map to increase my thinking about the world. I can add arrows to track the movement of people over time and, by doing so, a static map on a piece of paper comes alive in my mind. Add information about the biodiversity of plants and animals and I can think about the contribution of a location to life on earth.

We can call man-made objects artifacts because they are artifacts of human thought and knowledge representation. Knowledge is embodied in objects, which we can then extract upon interacting with them — the better knowledge is embodied, the more useful an artifact becomes for providing learning and insight. We have been using books to store and share knowledge and have amassed an impressive worldwide collection. Books gave us an enormous leap in turning on our embodied minds through interaction with written text and illustration. Any expertise on any subject can be stored in words exactly as an expert would explain a phenomenon if she were standing in front of us. And yet, the book lets us read at our own pace and even progress or review in a non-sequential manner — something might annoy an expert should we attempt to do so in their presence.

We have taken advantage of books as artifacts to become a well-read society — and we can continue to open and investigate books to realize all the different ways knowledge is embodied therein. Besides the arrangement of words, we find diagrams, tables, pictures, and images that encode information that isn't necessarily verbal in nature or that can be redundantly considered through multiple representations. With the advent of electronic book formats, we can add video, animation, and interactive applications within artifacts to spur on our thinking and insight. We have had such a good run with the book concept that our first attempt at internetworking content coined the phrase Web page as a common word for an atomic unit of consumption on the Internet.

There is nothing innate to the computing systems we use to surf the Internet to suggest that the content should be in a page format. Content can be presented in any manner that a series of scanning dots on a screen can present. As I tell my students that I prefer the potential of content presented as an application instead of as a page — and then show them what is possible with a focus on application instead of page — some seem to snap out of a reverie as if I were turning the world upside down. And yet, my first assumption when I learned about the World Wide Web was that we were going to share artifacts to educate each other — artifacts that would take advantage of computers, telecommunications, and dynamic screens for presentation. Constraining Web content to pages of knowledge seemed unnecessarily constrained, but we certainly had a lot of work to do to get our accumulated knowledge into an electronic format. It made sense to get all that knowledge in books and documents online so we could take advantage of the new delivery mechanism. Staring out with pages of information worked well enough to build interest in the Web, but we entrenched our expectations on the page format. Web designers found themselves creating artificial margins for Web pages and demanding new Web standards to make bounded content as attractive as books presented content.

If we eliminate man-made artifacts from the consideration of objects we interact with in order to think about the world, we realize how human-focused a book really is and how that perhaps separates our intelligence from the rest of the animal kingdom unnecessarily. Natural objects embody knowledge as well. As we see a bird fly from one branch to another, we have the opportunity to consider the design of wings as a subset of objects that provide flight. As we take a close look at a vine or a spider's web, we have the opportunity to learn about strength in objects. Thankfully, I see and hear about many new trends in using nature as a suggestion for design. I wonder how much we may have missed by falling in love with man-made artifacts first and foremost. Every natural object we encounter has the opportunity to teach us a lot about community and interconnection, even when an object's contribution seems limited in that effect.

Let's assume there is no reason to linger on the distinction between objects made by man and those that are not. Many suggest we might benefit from considering ourselves part of nature more often than we do. There are objects of scale that are not easily (or even possibly) experienced by our human scale. Subatomic particles aren't visible at human scale. Our human scale cannot directly experience the structure of a galaxy well from within one. There are good reasons to create human artifacts to help us with issues of scale. From that perspective, there's no surprise that I find maps so wonderful.

Another well-formed artifact is the periodic chart of the elements — an artifact I spent a whole year as a teenager getting to know and use for insight into understanding the nature of chemistry. The fact there is a natural organization for the elements in a chart form has made that artifact wonderfully popular without much follow-on debate as to other possible configurations. The chart almost seems to suggest it was given to us by the nature of the world we live in. As we look into the atomic and subatomic configurations possible with those elements, the structures of the artifacts we create seem less obvious — we begin to rely on evolving and redundant configurations of representation in the artifacts we make and share. Each different representation provides us the opportunity to think about the world differently — or generate insight differently depending on who is experiencing it.

Over time a community of researchers has come together to define an emergent field of complex data visualization. Some within the community try to define progress in visualization techniques along scientific lines. Some suggest visualization will always require the perspective of art. When both science and art refers to the same example as an example of superior visualization, the most definitive progress is made. As much as I want to find improvements to Charles Minard's data visualization of Napoleon's March on Moscow, I am not able to do so even though he made the original in the year 1869. My mind comes alive immediately when looking at that representation of complex data and I can agree that I get an immediate satisfaction of contemplating the data represented with the image he created. The geographic nature of the data helps me ground myself for understanding. The time aspect of the data helps me ground myself for understanding.

Many new additions to the field of visualization have been investigated thanks to our modern day electronic devices that let us interact with data displays. We can click, double-click, point, touch, drag, gesture, and speak to visualizations to get them to change data presentation to help us follow a train of thought. As we considered in chapter 3, our brain seems to be wired to focus on movement in our field of vision or range of hearing. Visualization techniques can take advantage of movement by moving the artifact in a pre-arranged manner or solely as a response to our interactions. The range of possible configurations for an artifact expands dramatically with the addition of changing spatial perspectives and elastic temporal extents. These new visualization capabilities tie intimately to mental abilities we gained over millennia thanks to the dynamically changing world in which we have lived. We find ourselves on the other side of the age of books — and yet we've encoded knowledge in books for so long that we have optimized our ability to use them for stimulating our minds. Books continue to be wonderful for their lack of specificity at times — where our imagination comes alive thanks to the lack of explicit presentation in that case.

We can now easily encode so much information in an artifact that a human brain can't attend to all of it at once. We may continue to do so as we provide large visualizations for groups of people to contemplate — especially when there is a natural segregation of duties inherent in attention. For example, people with different geographical expertise can share a dynamic map-based visualization. Negotiated interactions allow coordinated changes to presented real-time information. We can take advantage of programmed heuristics to suggest hints as to where a human should put her attention at any point in time.

As we come to consensus as to what makes an artifact better fit to inspire the human brain to thoughts and insights, we can begin to take advantage of new artifact production tools to create artifacts that improve the experience embodied minds get to improve their quality of life. This may seem backwards when so many of the artifacts produced in the industrial age were designed to improve quality of life by reducing the need to think and gain insight. A sponge may provide more insight and thought than a washing machine. I'm more interested in providing the mind understanding and insight as part of a quality of life metric, but I agree this perspective is luxurious without all the time and energy saving devices we have at our disposal for our survival that without which we'd have to spend time on survival.

The point is that our embodied mind now has a higher quality range of immediate artifacts it can spend time with in order to think and gain insight. The immediacy aspect is remarkable. We can't get any faster than immediate and we are rapidly approaching the technical ability to make all artifacts available immediately. If we agree all of them could be made accessible at the speed of light, we find our focus rapidly shifts to the nature of how they are packaged.

Simulation can then be described as a process by which we try to encode knowledge about phenomena in an optimal way so we can then interact with the simulations as if interacting with the real world — in order to tap the brain processes that were learning solely from the surroundings before books were available. Our spatial reasoning abilities served humans well. Our pattern recognition ability to identify objects and remember significant details about their roles in our daily lives helped us thrive or at least keep us alive. Simulation arouses those capabilities that contribute to new insights and deeper understanding with the added ability of adapting our perspective outsides the bounds of our human time and scale.

Our ancestors looked up at the skies at night and saw but one perspective of the universe. Thanks to satellites, telescopes and space probes, we have built up a perspective of the universe that is not tied to our earth-bound perspective. We can investigate other perspectives through the use of simulation. Simulation can allow us to increase our human scale to virtually experience a scale of equal size as our galaxy. We can create simulations where the whole universe can be explored from any perspective — using known objects and representative objects based on our best guesses as to what we would encounter far away from earth. Theories about the structure of our universe in the past and in the future can be demonstrated as simulations through spatial artifacts with which we can interact. Transitions through time in the structure of our universe can be demonstrated in accelerated time steps and slowed down on demand through interactive controls we use to turn on our brain to consider.

We can simulate changes in varying perspectives of time and space for phenomena that are much smaller than our human scale. We can experience a human cell by reducing our human scale to a virtual perspective that appears to be the same size as the cell being simulated. We can slow down cell processes to time steps that allow our brains to contemplate fast phenomena in time scales that we are more familiar in experiencing in our day-to-day experience of the world. We can speed cell processes up again to provide a perspective of how much work a cell performs on our behalf. Simulations presented as artifacts supporting tested hypotheses as to the purpose of cellular activity provide our brains the opportunity to experience suggested phenomena as visual representations for our deeper consideration — tying that experience to any other thoughts and insights we have experienced before.

Chapters 7, 8 and 9 provide case studies of simulations that change our human perspective in time and space in order to apply our thought processes to considering genres of phenomena. The artifacts embedded in the case study simulations encode knowledge about the domains being simulated. We are entering a phase of artifact creation where the ability to embed complexity into our artifacts is growing faster than our ability to comprehend the added complexity. When we experience being overwhelmed by complexity, disruptive emotions can interfere with our brain processes that are attempting to make sense, gain insight, and deepen understanding. As a result, many simulations are developed specifically to match the complexity that the intended audience of users is likely to thrive best upon encountering. Those who develop their ability to encounter complexity without interrupting an optimal flow to their contemplation, become an audience for which artifact developers can inject more complexity into artifact design.

The ability to make use of increasing artifact complexity relies on developing literacy with genres of artifacts. Reading literacy lets us read more complex language over time. Geographical literacy lets us read more complex maps over time. Simulation literacy lets us consider more complex simulations over time. Within each genre, we can become thematic specialists whereby our literacy is higher when the content matches the theme we've been exploring. If we explore astronomy through all the various artifacts we can find, we increase our reading, map, and simulation literacy for astronomical content. If we explore the human cell through all the various artifacts we find, we increase our reading, map, and simulation literacy for human cell content. Each theme we dive into provides a transferable increase in our overall literacy, but that amount of increase varies based on the similarity between themes.

Humans as a species have been increasing our literacy through the ages of perfecting artifacts as communication objects. Humans have been modeling and simulating phenomena for longer than recorded history. Anthropological hypotheses have suggested prehistoric cave paintings improved in communicated content as painters learned to take advantage of the effect a fire's glow had on visual perception of the paintings. Humans have been improving artifact creation methods ever since. Recently the tools we have made available to humans for modeling and simulating phenomena have allowed us to increase the complexity of our efforts well beyond anything possible before computers connected to advanced displays.

Software-based tools today afford us the opportunity to interact with simulated phenomena in ways that build our understanding over time. We can create software where complexity is added to a simulation over time. Today some researchers are trying to answer the question of how much complexity is optimal to add over time while other researchers are trying to answer the question of how much complexity each human should be exposed to as they build their literacy. New metrics like perceptive flow and cognitive flow attempt to anticipate when the brain is most likely to develop insights and understanding at the best rate. Video games have used the concept of levels to build player skills over time. Often, the video game does not provide the next level until the player has demonstrated requisite skill at the previous level. Artifact complexity designers have the opportunity to use levels within the interactive software in which they embed artifacts.

Much has been made of the cost and effort to build software tools in order to provide answers to questions asked by policy-makers and politicians — those who must act with respect to a financial bottom-line. Policy-makers and politicians rarely have the requisite time to linger, wonder, and ponder in an attempt to understand why the current answer might be the best possible answer at the time. Occasionally, if the answer is part of a pet project or urgent public consciousness, time is spent in getting to better understand the richness of the issue at hand. What other issues are tied to the issue and what cause and effect relationships exist between issues? I suggest it can be not only insightful, but also enjoyable to linger here. Lingering provides the brain time to develop literacy at a comfortable rate — one that aligns well with human pattern-recognition and memory time scales. With literacy comes a rich human experience that then responds well to an innate desire to understand the world in which we live. An interesting hypothesis to explore is how much that desire evolved by past environmental pressures that provided increased survival rates to those who expressed that desire in their daily thoughts and actions.

Having built my artifact literacy in thematic groups of phenomena through interaction with consumer products like Erector sets and Heath kits, I experienced the benefit of guided artifact creation. Those consumer products were thoughtfully designed to provide specific projects that could be attempted through documents that intermixed words and diagrams effectively. By doing projects in suggested order, I could build my literacy in an optimal progression for comfortable skill acquisition. When we acquired a general-purpose computer at home, I expanded my experience with artifact creation through software. Simulation video games like Sim City packaged modeling and simulation tools for the masses and the masses came to investigate those products with enough enthusiasm that, for many, the products lingered as available artifacts for us to experience the joy of modeling. For those of us who connect with memories of the joyful use of those products, we have an opportunity to better express where that source of joy comes from — as we understand any emotions of new insight through simulation. Helping others become mindful of the source of the joy of modeling and simulation for the benefit of human understanding is the goal of this book. Experiencing that joy could not come at a more valuable time for a humanity that is confronting a complex interaction with the natural and man-made world on a daily basis.

To fully absorb the potential of artifacts to embed knowledge for communication and consideration, it pays to invest in exploring the history of artifact creation with careful attention to time and dates. From cave paintings tens of thousands of years ago to the printing press hundreds of years ago to artifacts that take advantage of improvements in computer displays just years ago, the rate of competent artifact generation is accelerating greatly. Medical and chemical industries are thriving on new interactive artifact methods to explore drug designs for preventing and treating disease. Other industries are limping along, as effective mapping of knowledge to artifacts is not as easy to figure out. In that case, each new artifact requires a discussion to evaluate its effectiveness. Evaluation can include assessing the contribution that embedding artifacts into simulations can make. As simulations evolve successful processes for generation and use, artifacts can be shaped by the specific needs a simulation has for them.

There are a tremendous number of interesting examples of insights generated by those who embed artifacts into simulations. Many modeling and simulation case studies are neatly packaged as evidence to support explanation of a specific phenomena or test of a hypothesis. By understanding the contribution each artifact makes to an overall simulation, artifacts can improve through a better assessment vocabulary that supports a better assessment discussion.